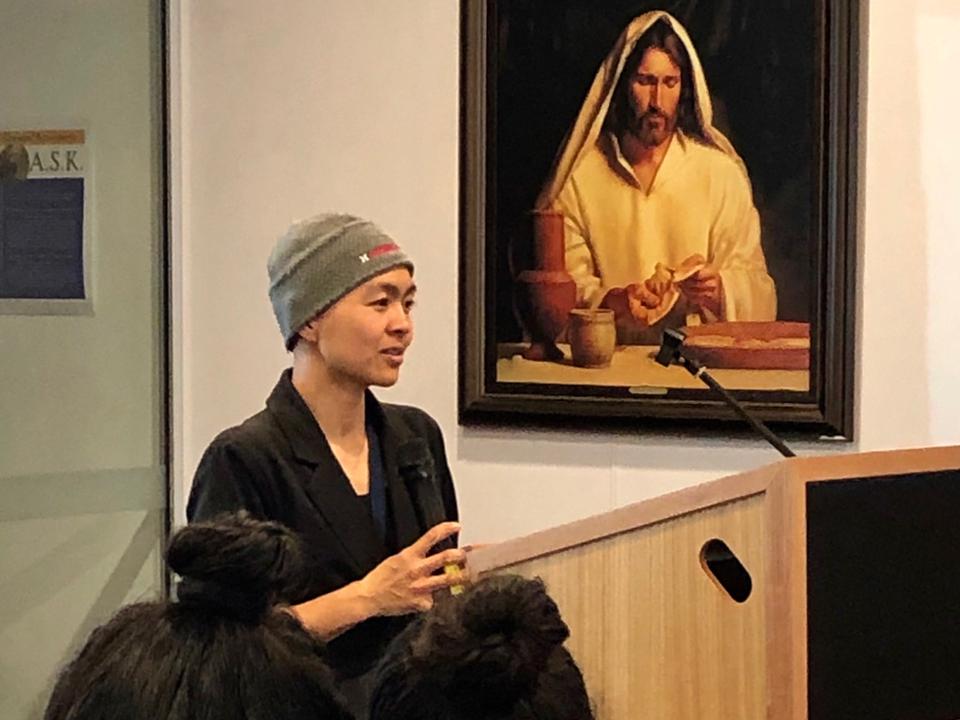

University of Auckland academic, Dr Melissa Wei-Tsing Inouye, was guest speaker at a devotional at The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints' Institute of Religion in downtown Auckland on Wednesday 14 August 2019.

The following are excerpts from her notes:

My earliest interfaith experience begins in the womb. Literally. My mother was in a prenatal education class in Costa Mesa, California, where a bunch of expectant mums got together to share experiences and socialize. My mother, a third generation Chinese American, and a Latter-day Saint, made friends with Cindy Knoernschild, a third generation Japanese American, an evangelical Christian. They hit it off. Joel, who became my childhood best friend, was born in late July; I was born a couple weeks later, on August 13.

Joel and I did so many things together, though I now realize that this was partly just because my mum and Auntie Cindy were such good friends. We played in the sandbox. We and all of our siblings went to the same co-op preschool. Our families went to the beach and went camping together.

One day in intermediate school, I stopped by the Knoernschilds’ house as usual to pick Joel up for our bike ride to school. He wasn’t quite ready, so I came into the kitchen and waited. On the counter I noticed a book: The Godmakers: A Shocking Expose of What the Mormon Church Really Believes. One of the endorsements on the back read, “This book reveals the subtle dangers of the fastest-growing religious cult in America. I believe every Christian should read it because no family is immune to this cult’s deception.”

I remember feeling surprised, for a couple of reasons. In the first place, I hadn’t realized that people disliked and mistrusted my faith tradition so much that they went to the trouble to write a book about it. In the second place, I was surprised to find these angry voices shouting from the kitchen counter of our family friends. Is this what Auntie Cindy and Uncle Joe thought of us?

The years passed and the Knoernschilds continued to be our very best family friends, books on kitchen countertops notwithstanding. I came to realize that for our family friendship, religion was both a point of tension and a point of commonality.

On the one hand I realized that evangelical Christians were generally very suspicious about Mormons. On the other hand I saw that my parents and Auntie Cindy and Uncle Joe shared aspects of their faith with each other. One Easter morning, we joined the Knoernschilds for their megachurch’s sunrise service in a big stadium. When we shared meals together, we prayed, each in our own fashion. Once, in a family discussion about keeping the Sabbath day holy, my father observed that different families and different religions had different ways of keeping the Sabbath. Somewhat enviously, he pointed out that Uncle Joe belonged to a “surfing fellowship.” On Sunday mornings, instead of getting into a white shirt and tie and sitting in class for three hours, Uncle Joe and his friends went out to the beach in the wetsuits, shouted, “This is the day the LORD hath MADE!” and plunged into the waves.

As a child, our family friendship with the Knoernschilds was my first experience of the perils and possibilities of cultivating deep relationships with those whose beliefs differ from one’s own. Throughout it all, even during the awkward silences, what was most evident is that Auntie Cindy was one of my mother’s very best friends. When my mother passed away in 2008, Auntie Cindy spoke at her funeral, standing behind the pulpit in the Latter-day Saint chapel located a couple of blocks from both our homes.

This early childhood experience set a baseline for my future encounters with people of other faiths. Of course, all of my childhood experiences were actively shaped by the choices my parents made, and the example they set for their children. My mother and father were extremely active within our close-knit Latter-day Saint congregation, but also cultivated friendships with many different kinds of people in the broader community. I remember my father telling me to “never make fun of someone else’s righteousness.”

Throughout the course of what I will call a short but eventful life (I turned forty yesterday, so I know I’m a spring chicken compared to many adults), I’ve had the opportunity to cultivate wonderful friendships.

I value my Latter-day Saint faith. It’s made me who I am as a scholar, an athlete, a parent, and a friend. But my faith, and who I am, have also been shaped by the good examples and devoted practices of evangelical Christians, Jews, Muslims, Buddhists, and others (atheists, for that matter).

We live in a world of strife, factionalization, separation and polarization. The fabric of society threatens to tear apart, on a local, national, and global scale. It is not enough to simply say, I love everyone. It is not enough to say, I believe that we are all children of God. It is not enough to say, every person is special. Espousing beliefs is not enough. The world has enough beliefs, in every shape and size. What the world needs now, is action.

I believe that people of deep religious or spiritual convictions are well-positioned to take on the most difficult challenges and disagreements that currently divide humanity. This is not because religious people have superior knowledge or exemplary morality, for we know that we are all imperfect, and we all fall short. It is this imperfection, and the tools that religious communities have developed to grapple with imperfection, that give us experience and resolve in working through difficult human challenges. Our covenants and commandments, backed by God’s power, can fortify us. It takes courage to try to figure out how to love one’s neighbour as oneself when that neighbour endorses a political position one finds reprehensible. It takes discipline to hold one’s tongue and try to listen to what another person is saying. It can be frightening to welcome a stranger, or feed someone who is hungry, or visit someone in prison, but Latter-day Saints believe that this is what Christ has commanded us to do. Obedience to these great commandments—to love God, and to love one’s neighbour—is not something we can opt-out of. We just have to do it.

The action that we need, therefore, is reaching out to others—spending time with them, visiting them in their own places, understanding where they came from.